29 18th and 19th Century Art

18th Century American Painting

American art of the 18th century might be considered to have suffered from an inferiority complex. The colonial population in the decades before the American Revolution of 1776 – and much during and after the war – thought of itself as English. America sent raw material to England and received goods manufactured at the new factories that stood at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in return. For many of about-to-be newly minted Americans, English goods were a mark of status and underscored their ties to the Crown. Benjamin Franklin wrote about his wife’s purchase of a china bowl and plate spoon for his breakfast as a rhetorical statement of her husband’s importance.1 This reliance on English goods as examples of “civilized” behavior would impact the early American artists as well.

American artists of the 18th century would have had little exposure to the kind of painting that was available to the public in England and Europe at large. There were no museums in America until 1773, and the early institutions were more in the nature of ethnographic or natural history museums than they were like the Louvre.2 In 1784, C.W. Peale opened the Philadelphia Museum which was largely a collection of natural history curiosities, but initially it did have a display of forty-four portraits that depicted “worthy personages” of America’s Revolutionary era making it perhaps the first art museum in America. Peale’s son, Rembrandt, was himself a painter of seventy-nine portraits of George Washington.

More importantly, there was no tradition of the great art academies that had existed in Europe since the 16th century. The Academy and Company for the Arts of Drawing in Florence was begun by Cosimo de’ Medici in 1563. It should be noted that while a number of women artists created careers of note throughout art history it wasn’t until late in the 19th century that they were admitted to most art academies. One of the foremost reasons was the belief that it was inappropriate for women to take part in life drawing classes with an unclothed model. While some wealthy colonialists had undoubtedly brought paintings with them from Europe, these were not available for public consumption. American artists were essentially self-taught and tended to be itinerant, or traveling, artists relegated to certain parts of the country doing all kinds of work for hire from commissioned portraits to signs over tavern doors. These early American artists were called “limners”and most are not known by name.

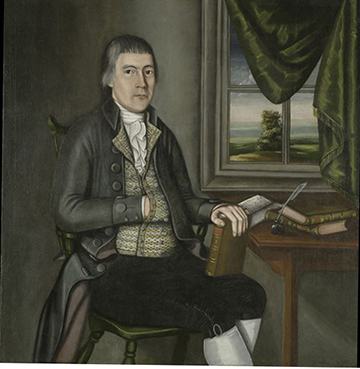

Art historians have made an effort to identify some of these artists, however. The so-called Beardsley Limner whose portraits of Doctor Hezekiah Beardsley and his wife, Elizabeth, were executed around 1785-90 is one of the more celebrated. Some have attributed the work to a Connecticut pastel artist, Elizabeth Bushnell Perkins (active 1771-1831), but others don’t find the style convincing. In any event, the portraits of the doctor and his wife are typical of the early American limner style.

Persons of enough means to commission a portrait would have been concerned about what those paintings said about them. Dr. Beardsley is shown in sober clothing but of good quality with a silver buckle at his knee. He is literate as evidenced by the book on the table in front of him – Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire – and the pen and inkwell with which he makes notes. Out the window behind him we are shown an expanse of land which may belong to the doctor, or may simply be there to suggest his presence in the wider world.

Elizabeth Beardsley is also shown in clothing that suggests wealth. Her gown appears to be shiny like satin or silk, and her scarf and mobcap is of transparently fine cloth. She wears a cameo on a ribbon and has in her hand an open book and two pink flowers. The dog at her side is probably there to suggest fidelity as images of dogs have done in iconography for centuries; the fruit implies fecundity or possibly wealth – the ability to purchase imported fruit. Out her window, however, we have a different scene from that of her husband. There is a bush with the pink flowers from which the two she holds would seem to have come, there is a garden path but it ends at a high wooden fence. Unlike Doctor Beardsley’s access to the world at large, his wife’s world ends at her garden gate.

Elizabeth Beardsley is also claiming credit for literacy. In her lap is a copy of Reverend James Hervey’s Meditations and Contemplations in which he suggested that “Ye flowery Nations, Ye must all decay,” possibly referenced by the pink flower she holds. 3 Together the texts suggest that the Beardsleys were intellectuals with a critical eye to the fortunes of the new American nation.

Both figures are typical of the limner style of painting. They are stiff and painted with limited modeling giving them the flatness of a medieval icon. Both figures inhabit a limited, but relatively believable, space and there is a flatness to the perspective outside the windows. The fabric of Elizabeth Beardsley’s dress is indicated by the horizontal areas of linear shadow giving the indication of shine without the actual illusion of it. E. H. Gombrich has described the practice of “making” and “matching” in Art and Illusion.4 He suggests that artists learn from copying the techniques of other artists; they begin with an idea of whatever is in front of them and then proceed to match the original schemata to create a more perfect illusion. Without the benefit of learning the matching techniques American limners were stuck at the conceptual, or making, stage. While art theory may have moved on from Gombrich’s ideas, it is an effective way to describe the result of many early American artists’ production.

One resource available to early American painters might have been the prints that came to American with the ships from England. Reproductions in engraving or etching from artists like Anthony van Dyck would have shown artists the linear equivalent of creating a painterly shine on fabric and it is that kind of making we see in Elizabeth Beardsley’s dress.

John Singleton Copley

Barbara Novak has called John Singleton Copley (1738-1815) the first painter to create a truly American vision.5 As Novak presents the artist’s early career, he effectively marries American conceptual materialism with a desire to paint like the Europeans.

Copley was born into an Irish-Anglo immigrant family, probably in Boston. His father died when he was young and his mother remarried the artist-engraver Peter Pelham. It seems that Copley learned engraving and some painting from his stepfather, although he was largely self-taught. He must have had the example of prints from England and the continent since he was aware from an early age of the inadequacies of both American art and patronage. In November of 1766 he wrote to ex-pat artist Benjamin West, “In this Country as You rightly observe there is no examples of Art, except what is to [be] met with in a few prints indifferently exicuted, from which it is not possable to learn much.” Note that many early Americans wrote equally badly.

Still, Copley managed to give the American gentry what it wanted, and that was – often – the appearance of English nobility.

His portrait of Mrs. Jerathmael Bowers, wife of a well-to-do Quaker in Massachusetts, shows the method of copying – or matching – from a print of another painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds’ subject would have been attractive to American colonialists concerned with status; Lady Caroline Russell was the wife of George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough and would be an ancestor of both Princess Diana (Spencer) and Winston Churchill. In addition, Sir Joshua Reynolds was himself a founder and the first president of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts.

You can see the American artist copying not just the composition of the Reynolds, but the costume (although he changes the color but if he’s working from a print he would not have known the original), and even the spaniel. If you compare the two carefully you will see that Copley’s shadowing, the chiaroscuro in the modeling of the figure, the highlights on the dress all are carefully done but harder-edged than the original. Too “liney” as West would say about another Copley painting sent to England and shown in one of the Royal Academy’s exhibitions.

Novak has suggested that during his colonial phase Copley was concerned with the conceptual objectness of things and treated the images of people the same way.6 It was this concreteness without the nuance of illusion that gave his portraits a frozen quality, even as his ability to capture likeness and to generate an increasing naturalism in surfaces progressed. However, Novak notes that in portraits of persons he knew better and which he painted in a more informal manner, like the portrait of Paul Revere from ca. 1768—70, there is more of a suggestion of personality behind the image – a “living portrait”.7

Copley managed to make his way to England in 1774. He traveled on to Italy and France, observing the examples of European history painting that he had so long desired to see. In England, West and Reynolds provided the young American with entry into the artistic circles of London and an introduction to the techniques of the Grand Style of European art.

One of Copley’s more successful paintings after his European education was a commission he undertook for English businessman Brooke Watson in 1778. The painting recounts an event in the then cabin-boy Watson’s narrow escape from the jaws of a shark in Havana, Cuba. He did lose a leg to the shark and Copley gives a suggestion of pink in the water where the right leg is submerged. This painting incorporates both the action and Gothic horror of the moment with the survival of his American recreation of waves with hard edges and a shark apparently known only from written accounts (and presumably from Watson’s remembered eye-witness account!). Arguably, something was lost as Copley became more adept in the European Grand Style of painting, although his example is instructive in the differences between the early American artists and their European counterparts.

There are many other American artists who made the pilgrimage to Europe, and many brought what they learned back to America with them. Gilbert Stuart, the painter of the George Washington that we all have on our dollar bills, was one such. Others, like West, remained in England for their entire careers. The inability of American painters to make the genre of history painting their own was partially accounted for by the fact that America didn’t have – or at least didn’t feel it shared innately and authentically – the literal history that classical European history painting embodied. It wasn’t until the 19th century that American artists would find their own version of history in America itself.

19th Century American Painting

In 1791, Chateaubriand – who had left France disgusted with the French Revolution – traveled through the newly made country of America writing about what he saw. He wrote, “Nothing is old in America except the trees,” and in that statement captured what American artists of the 19th century would understand as the American answer to European history painting – landscape.8 Throughout the early part of the century American painters would concentrate on capturing the American landscape in all its variety. One artist who embodies the new aesthetic of America, as Copley did in the previous century, was Thomas Cole. Cole himself was born in England, but he came to America with his family in 1818 at the age of 17. He lived first in Ohio, then Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and in 1825 moved to Catskill, New York, where he was a founder of the Hudson River School (a style of painting or subject matter, not an actual institution). Cole worked as an engraver and was originally a portraitist, but by the time of his removal to New York he was concentrating on landscape. As a mature artist he would paint allegorical works which incorporated landscape with ideas not unlike those of the European history painters. But it was his influence on landscape artists like Asher B. Durand and Frederic Edwin Church that would be most significant in art history. Like earlier European artists, notably Poussin and Claude, Cole would sketch from nature in the outdoors but finish his canvases in the studio. In 1842, Cole sent back to Europe with the intention of making the Grand Tour to study the Old Masters. He also made paintings of the European landscape on that trip.

The Oxbow

Most professional men in the early 19th c. in America belonged to the Freemasons, a sort of private club for privileged white men – George Washington was Grand Master of his lodge. David Bjelajac has noted that Cole’s Freemasonry played a part in the imagery he incorporates in the Oxbow.9 Completed as a commission for his patron, Luman Reed, and intended for the annual exhibition in 1836 at the National Academy of Design. Cole thought of it as “a view” and easier to execute than the multiple figured canvases of his Course of Empire series. The Oxbow, or View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm, was a popular tourist site in New England and so one that many people would know. Cole used a larger canvas that he had in his studio than a landscape view might normally have been made on. At 51 1/2 x 76” it approached the size of a history painting. But this was no simple landscape; Cole used the actual scene on the Connecticut River as an opportunity to include a number of larger ideas. The painting is dived diagonally by the green hillside and the dark clouds in the sky. The land on the right side of the divide is seen in the distance as a tame, cultivated space with orderly fields and husbanded trees surrounding the river. The oxbow of the title takes its name from the actual feature of the river as it loops back on itself and suggests the yoke on a team of oxen. The left side of the scene is wild nature with a blasted tree in the foreground that leads our eye upward to the storm clouds that seem to be moving to the left. Cole has created a literal description of the mindset of Americans at this moment for whom the taming of the wild land was a God-given duty and one that would find political expression in Manifest Destiny. The term was a controversial one that would be used to justify American imperialist expansion into the western territories of Native Americans. Bjelajac has noted the faint areas on the distant hill that seem to be the Hebrew letters for either “NOAH” (right side up) or “SHADDAI” (or Almighty when read upside down, as if from above). (Bjelajac, 70). In any event, this gloss of Christian religiosity imposed on the landscape would have been understood and appreciated by the American viewers of the 19th c.

Frederick Edwin Church

The son of a wealthy family, Church was born in Hartford, Connecticut, and became one of the most famous American artists of the 19th century. He studied for two years with Thomas Cole, and created monumental composite landscapes that joined scenes and sketches from various locations into often fantastic views. Church’s – and many of Cole’s large canvases of his series – were exhibited to take advantage of the public’s desire for spectacle. A large exhibition space would be rented and the paintings displayed for the public at large to see for an entrance fee.

As a second-generation Hudson River School artist, Church was painting in the Romantic landscape tradition that would include artists in Europe like Caspar David Friedrich, John Constable, and J.M.W. Turner. Burke’s idea of the Sublime – the awe inspired in human beings by the majesty of God’s creation – would inspire these detail-rich scenes and would appeal to the Protestant religious leanings of early 19th c. Americans.

Church would travel widely including two trips to South America in 1853 and 1957 where his paintings like The Heart of the Andes (1859) would include a multitude of plants and animals, each recognizable and scientifically correct in detail. At a time when the writings of explorer-naturalists like Alexander von Humboldt and later Charles Darwin were capturing the popular imagination, Church’s canvases brought crowds of thousands into the gallery where he displayed it as if it were a window looking out onto the Andes with “natural” lighting from overhead. He eventually sold it for $10,000 which was the highest price ever paid for an American painting to date.10

The Luminists

In New England another group of painters was creating a uniquely American style of painting, although it, too, was based in part on a European model. Barbara Novak has described the large, Baroque paintings of Cole, Church, and Bierstadt as “Grand Opera,” and the more modestly sized, quiet, glowing canvases of the Luminists as the “still, small voice.”11 Martin Johnson Heade, Fitz Hugh Lane, and John F. Kensett among others found in the watery New England landscape the visual correlative of the era’s transcendentalist preoccupation. Many of these artists worked in both the more homely Hudson River style and some Hudson River artists – including, on occasion, Cole and Church – created work in the glowing Luminist tradition, but the Luminist paintings of the New Englanders of the 1860s were working in a style that drew less from the theatrical European history paintings and more from the Baroque Golden Age of Dutch maritime paintings. Like those Dutch paintings which had been created in a modest size scaled to the domestic interiors of the wealthy Netherlandish merchant patrons, the Luminists worked primarily on horizontal canvases with glazes of oil paint that seemed to glow from within (luminists).

“Standing on the bare ground,– my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, — all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball. I am nothing. I see all. The currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.”12 This quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson seems to describe the intention of the Luminist painters in their works of light and stillness.13 The Luminists choice of a horizontal format for their paintings echoed the horizontality of the quiet ocean or lakes that were their usual subject matter. The concept of the Sublime, Burke’s idea about the presence of God in the landscape, in these works becomes less awe-inspiring or terrifying, and more spiritually immersive – like gradually sinking into a golden pool of God.

This painting of Lake George, New York, by Kensett is a model of Luminist style in another mood. Here storm clouds reminiscent of Cole’s Oxbow scud from right to left in the distance. Even with the similarities of rocks and trees framing the left of the painting and a brighter vista in the distance, Kensett’s painting still seems frozen in a moment that has little to do with the ambitions of human beings.

Edmonia Lewis

The history of African-American artists during the 19th century paralleled the struggle of all Black Americans at that fraught time. Black people in general in the periods both before and after the Civil War were most often pictured racially stereotyped in both appearance and the activities they were shown engaged in. Despite this, there were a number of African-American artists who attempted to show a more genuine image of Black history and to create work that was equally significant with that of any artist. These artists were ignored by art history for years, but increasingly their voices and eyes are providing a clearer picture of early American art. One inspirational woman who has become part of modern art history and the history of women in general is Edmonia Lewis. Lewis was the child of an Afro-Haitian father and Native American (Mississauga Ojibwe) mother in upstate New York in or about 1844. Lewis was inconsistent in her statements about her early childhood and often chose to amplify her Native American heritage including the name she was apparently given, Wildfire. She was born free, and while her parents died when she was young her half-brother made a fortune in the California goldrush and saw that she received an education. After experiences at some preparatory schools, Lewis attended Oberlin College, one of the first higher-learning institutions in the U.S. to admit women as well as persons of different racial identities. She was subject to a number of apparently discriminatory episodes at Oberlin and left before graduating. She moved to Boston, a Northern town with many important abolitionists in residence, and began work as a sculptor. After facing rejection by several male artists for tutelage, she was taken on for a time by Edward Augustus Brackett, a moderately well-known sculptor. In 1864 she opened her own studio.

Lewis made money doing portrait medallions of famous abolitionists and figures from the Civil War. Despite some success with these and some Native American-themed works Lewis left America for Rome in 1865. She wrote, “I was practically driven to Rome in order to obtain the opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color. The land of liberty had no room for a colored sculptor.”14

There was a large community of ex-patriot women artists in Rome in the 1860s. Henry James referred to them as both “that white marmorean flock” – marmorean signifying marble since many were sculptors – and “that strange sisterhood of American lady sculptors who at one time settled upon the seven hills [of Rome].”15 While Lewis found some measure of society and freedom from oppression, she still faced the same issues of patriarchy as evidenced by James’ text as did the other women artists.

There is great individuality in Lewis’ work compared to other Neoclassical or Romantic artists. Her subjects were largely related to either her Native American heritage or that of Blacks in history. Her style, however, has frequently been criticized for the erasure of those racial characteristics that might have made the work more politically insistent.

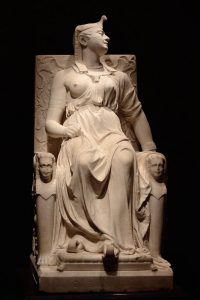

Her most recognized work is currently in the Smithsonian Institution. In 1876, Lewis created a monumental sculpture of the Egyptian pharaoh Cleopatra for the Centennial Exhibition that was held in Philadelphia. The work was very well-received although after the exhibition closed it failed to sell. From storage it eventually went on to decorate a saloon, and then to mark the grave of a racehorse named “Cleopatra”. When it was finally donated to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 1994 it required extensive restoration.

Lewis’ Cleopatra is a substantial figure, head back and eyes closed in death, on an elaborate throne in Egyptian motif. While typically exhibiting the features of a white – or racially neutral – Neoclassical figure, the sculpture exhibits the softly rounded fleshiness of Lewis’ other figures with graceful drapery that leaves one breast revealed, an image which recalls medieval versions of the Virgin Mary breast exposed in healing or charity; Delacroix depicted his Liberty leading the people with breasts exposed, possibly to underscore her function as allegory or to represent freedom being nurtured by France.16

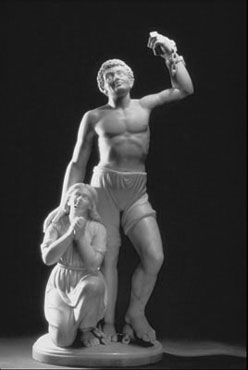

Lewis created this sculptural group to commemorate the ratification of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery in the United States. Little is known about the end of Lewis’ life, but her work commemorates a creative life carved out of the oppressive reality of 19th c. America.

Robert S. Duncanson

Other African-American artists made significant work during the 19th century. Robert S. Duncanson was the child of a white Canadian of Scottish ancestry and a black mother. He was one of the American landscape artists to achieve national recognition. He worked mainly in the 1850’s and 60’s and modeled his paintings after those of the European master Claude Lorrain which he saw on a brief trip to Europe in 1853. One of his early patrons was the abolitionist Nicholas Longworth of Cincinnati who was also a supporter of Hiram Powers, a white sculptor living and working in Florence, Italy, at the same time that Edmonia Lewis was in Rome.

Duncanson’s paintings were similar to those of the Hudson River painters Cole, Durand, and Church. Some of the work is imaginative like Cole’s Course of Empire series, but exhibit less of the drama of the Sublime in favor of a more restrained and almost Classical remove.

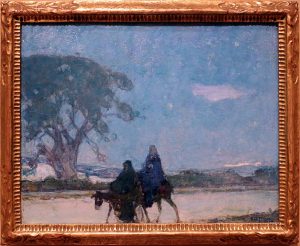

Henry Ossawa Tanner

Like Lewis and other African-American artists, Henry Ossawa Tanner moved to Europe to practice his art during the 19th c. Unlike Lewis, Tanner moved to Paris in 1891 and lived and worked there among the Impressionists for the rest of his life. Tanner had been a pupil of Thomas Eakins at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, the only black student in 1879. Tanner has written of the prejudice he experienced at the hands of his fellow students, although he became friends with Eakins and Robert Henri, later founder of the Ashcan School in New York City. I was extremely timid and to be made to feel that I was not wanted, although in a place where I had every right to be, even months afterwards caused me sometimes weeks of pain. Every time any one of these disagreeable incidents came into my mind, my heart sank, and I was anew tortured by the thought of what I had endured, almost as much as the incident itself.17

In France he became best known for religious subjects and visited the Middle East at one point. His most acclaimed work in the United States was not a religious subject, however, but a domestic interior with an older black man teaching a child to play the banjo. At a moment in America when the most common images of African-Americans were disparaging clichés of minstrelsy and other racist tropes, this sensitive and human scene was created in a muted palette with soft lighting falling on the two figures.

Tanner would be recognized in France with one of its highest honors, the Legion of Honor, for his work over a long career.