18 Early Christianity and Byzantine Art

Constantine seized sole power over Rome to establish authority and stability, and then moved the capital from Rome to Constantinople.

Key Points

- Constantine reigned from 306 to 337 CE. He managed to re-establish stability in the empire and rule as a single emperor, legalize Christianity, and move the imperial capital to the newly-formed city of Constantinople.

- The Arch of Constantine, a triumphal arch commemorating Constantine’s victory over Maxentius, makes use of spolia from monuments dedicated to Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius.

- Constantine completed the Basilica Nova, the construction of which was begun by his rival, Maxentius. This massive concrete building displayed the impressive power and authority of Constantine.

- At one end of the Basilica Nova sat the Colossus of Constantine: over 40 feet tall and made of marble, brick, wood frames, and bronze gilding. The Colossus further emphasized the sole authority, control, and power held by Constantine.

- After Constantine relocated, the city of Rome became vulnerable to barbarian hoards who pillaged local monuments and buildings. Outside Rome, Constantine oversaw the construction of the imperial district of Constantinople and the Aula Palatina in Trier (present-day Germany).

Key Terms

- nave: The central area of a basilica.

- apse: A semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault, also known as an exedra.

- colossus: A statue of gigantic proportions. The name was especially applied to certain famous statues in antiquity, such as the Colossus of Nero in Rome, and the Colossus of Rhodes, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

- basilica: A building having a nave with a semicircular apse, side aisles, a narthex, and a clerestory. The Roman design of the basilica became the model for Christian churches.

- spolia: The reuse of building material or decorative sculpture for new buildings or monuments. Latin for spoils.

Constantine

The far-flung Roman Empire began to come apart and by 410 CE the last Roman legion had left Britain. Divided internally and pressed from invaders from the north, numerous individuals vied for the title of Emperor. By 312, two of these, Constantine and Maxentius, were engaged in open hostilities, culminating in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, in which Constantine emerged victorious.

Although he attributed this victory to the aid of the Christian god, he did not convert to Christianity until he was on his deathbed. The following year, however, he enacted the Edict of Milan, which legalized Christianity and allowed its followers to begin building churches. With the Christian community growing in number and in influence, legalizing Christianity was, for Constantine, a pragmatic move.

Following a rebellion from Licinius, his own co-emperor in 324 CE, Constantine eventually had his former colleague executed and consolidated power under a single ruler. As the sole emperor of an empire with new-found stability, Constantine was able to patronize large building projects in Rome. However, despite his attention to that city, he moved the capital of the empire east to the newly founded city of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul). For a time, a Christianized Roman Empire in the East will flourish as Byzantia.

Basilica Nova and the Colossus of Constantine

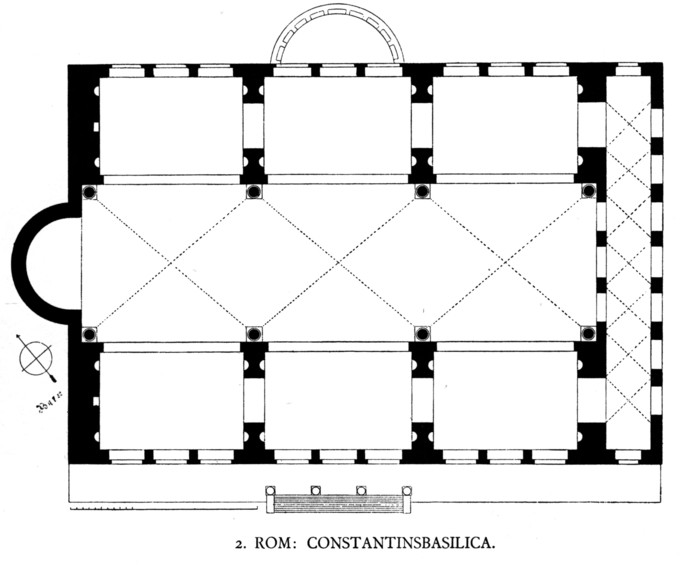

When Constantine and Maxentius clashed at the Milvian Bridge, Maxentius was in the middle of building a grand basilica. It was eventually renamed the Basilica Nova, and was located near the Roman Forum. The basilica consisted of one side aisle on either side of a central nave.

When Constantine took over and completed the grand building, it was 300 feet long, 215 feet wide, and stood 115 feet tall down the nave. Concrete walls 15 feet thick supported the basilica’s massive scale and expansive vaults. It was lavishly decorated with marble veneer and stucco. The southern end of the basilica was flanked by a porch, with an apse at the northern end.

The apse of the Basilica Nova was the location of the Colossus of Constantine. This colossus was built from many parts. The head, arms, hands, legs, and feet were carved from marble, while the body was built with a brick core and wooden framework and then gilded.

Only parts of the Colossus remain, including the head that is over eight feet tall and 5.5 feet long. It shows a portrait of an individual with clearly defined features: a hooked nose, prominent jaw, and large eyes that look upwards. Like the porphyry (a type of purple marble) bust of Galerius, Constantine’s portrait combines naturalism in his nose, mouth, and chin with a growing sense of abstraction in his eyes and geometric hairstyle.

He also held an orb and, possibly, a scepter, and one hand points upwards towards the heavens. Both the immensity of the scale and his depiction as Jupiter (seated, heroic, and semi-nude) inspire a feeling of awe and overwhelming power and authority.

The basilica was a common Roman building and functioned as a multipurpose space for law courts, senate meetings, and business transactions. The form was appropriated for Christian worship and most churches, even today, still maintain this basic shape.

Rome after Constantine

Following Constantine’s founding of a New Rome at Constantinople, the prominence and importance of the city of Rome diminished. The empire was then divided into east and west. The more prosperous eastern half of the empire continued to thrive, mainly due to its connection to important trade routes, while the western half of the empire fell apart.

While Byzantium controlled Italy and the city Rome at times over the next several centuries, for the most part the Western Roman Empire, due to being less urban and less prosperous, was difficult to protect. Indeed, the city of Rome was sacked multiple times by invading armies, including the Ostrogoths and Visigoths, over the next century.

The multiple sackings of Rome resulted in the raiding of the marble, facades, décor, and columns from the monuments and buildings of the city. Parts of ancient Rome, especially the Republican Forum, returned once again to the cow pastures that they originally were at the time of the city’s founding, as floods from the Tiber washed them over in debris and sediment.

Constantinople

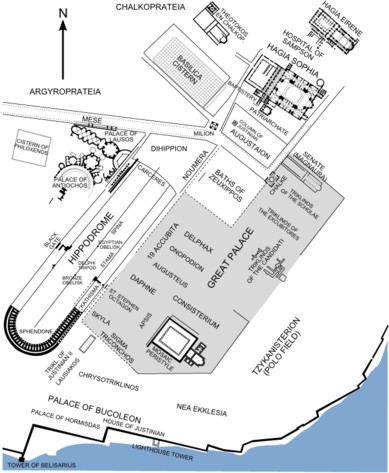

Constantine laid out a new square at the center of old Byzantium, naming it the Augustaeum. The new senate-house was housed in a basilica on the east side. On the south side of the great square was erected the Great Palace of the Emperor with its imposing entrance and its ceremonial suite known as the Palace of Daphne.

Nearby was the vast Hippodrome for chariot races, seating over 80,000 spectators, and the famed Baths of Zeuxippus. At the western entrance to the Augustaeum was the Milion, a vaulted monument from which distances were measured across the Eastern Roman Empire.

The Mese, a great street lined with colonnades , led from the Augustaeum. As it descended the First Hill of the city and climbed the Second Hill, it passed the Praetorium or law-court. Then it passed through the oval Forum of Constantine where there was a second Senate house and a high column with a statue of Constantine in the guise of Helios, crowned with a halo of seven rays and looking toward the rising sun. From there the Mese passed on and through the Forum Tauri and then the Forum Bovis, and finally up the Seventh Hill (or Xerolophus) and through to the Golden Gate in the Constantinian Wall.

Early Christian Iconography

Christianity was only one of a number of “new” religions in Rome at the end of Empire. It did prove to be the most successful. Literally an underground religion in the days before Constantine’s Edict of Milan, Christian congregations gathered in private homes and in the underground burial tunnels, or catacombs, of the city. These necropolises, or cities of the dead, were originally located outside the walls of the city, but larger spaces were also created underneath the city eventually. One of the spaces used for early Christian worship is underneath St. Peter’s. It is there that this fragment of early Christian mosaic is located.

In this mosaic, a youthful Christ is shown in a chariot being pulled by two white horses and surrounded by a decorative border of grapevines. Christian teachings refer to the East as the direction from which Christ ascended and where he will return in the Second Coming. Most Christian churches are organized with the apse and altar in the East. This was also the direction the pagans prayed to because it was the direction from which the sun rose. Here we see Christ conflated with Apollo the Sun God whose chariot drew the Sun from East to West everyday for the Greeks. Grapes and grapevines were associated with the Greek God Dionysus (Roman Bacchus), but here the Christians have appropriated the image to refer to the lines from the Bible that equate Jesus with the one true vine from which all things come. Without traditional images to rely on it is reasonable to expect the early Christians to take their imagery from sources they knew – the Greek and Roman deities. It is also strategic for a new religion, looking for converts, to use images and ideas from the existing tradition and overlay them with their own meaning.

The same impulse may have been behind the early Christian churches. In 313 when Constantine made it possible for all religions to worship openly, structures had to be designed to fit the Christian congregational style. Believing his reign to be the gift of the Christian god, Constantine financed a number of imposing new structures including the Old St. Peter’s. It was built on the site in Rome where it was believed the apostle Peter had been buried. Many searches underneath the new St. Peter’s have been conducted in an attempt to locate the relics of the Saint, but nothing conclusive has been found. Old St. Peter’s was torn down in 1506 to make way for the current St. Peter’s, and no images of the old church survive. Historical accounts and another structure which was said to be visually similar, St. Paul’s Outside the Walls, stood until the 19th century and provided some ideas about what the older structure must have been like.

Architecture of the Early Christian Church

After their persecution ended, Christians began to build larger buildings for worship than the meeting places they had been using.

Key Points

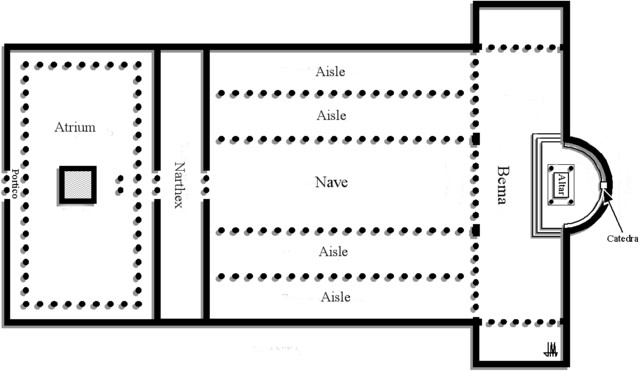

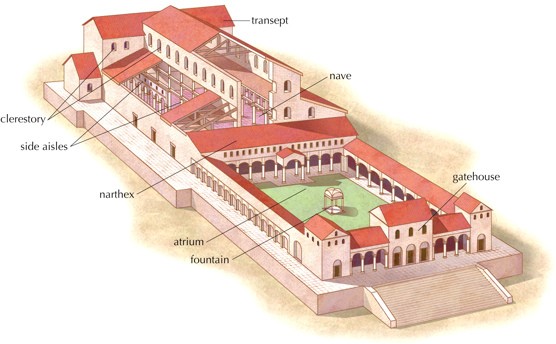

- Architectural formulas for temples were unsuitable, so the Christians used the model of the basilica, which had a central nave with one aisle at each side and an apse at one end. The transept was added to give the building a cruciform shape.

- A Christian basilica of the fourth or fifth century that stood behind an entirely enclosed forecourt that was ringed with a colonnade or arcade. This forecourt was entered from the outside through a range of buildings that ran along the public street.

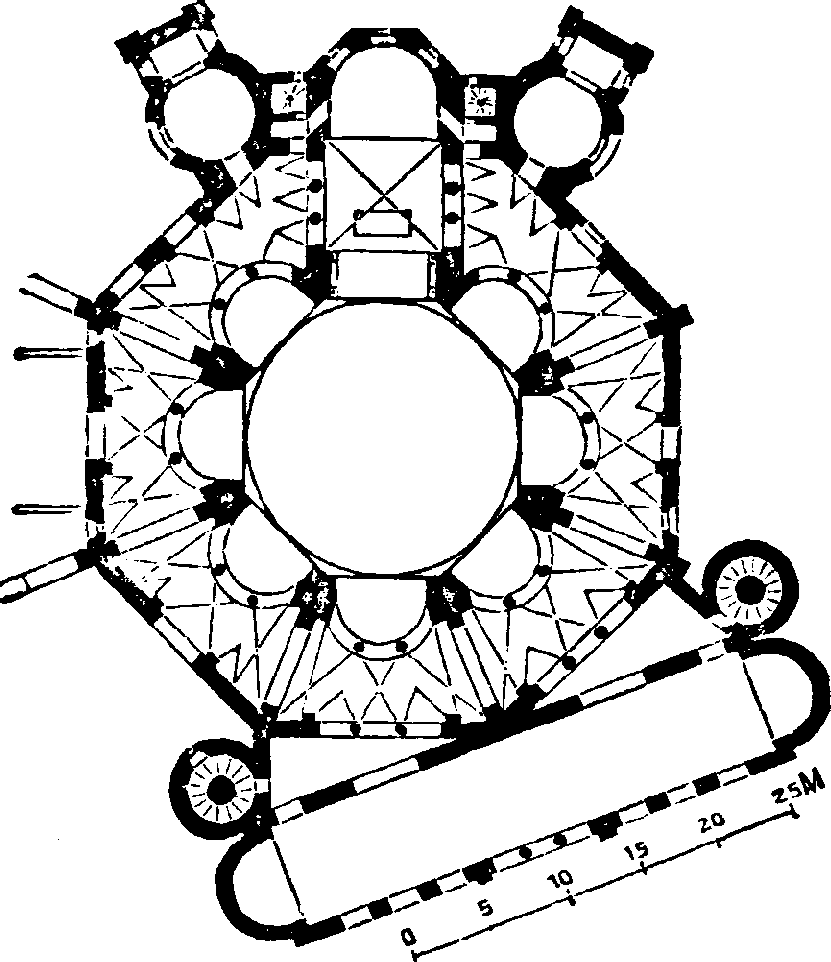

- In the Eastern ( Byzantine ) Empire, churches tended to be centrally planned, with a central dome surrounded by at least one ambulatory.

- The church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy is a prime example of an Eastern, centrally planned church.

Key Terms

- lunette: A half-moon shaped space, usually above a door or window, either filled with recessed masonry or void.

- presbytery: A section of the church reserved for the clergy.

- theophany: A manifestation of a deity to a human.

- prothesis: The place in the sanctuary in which the Liturgy of Preparation takes place in the Eastern Orthodox churches.

- fascia: A wide band of material that covers the ends of roof rafters, and sometimes supports a gutter in steep-slope roofing; typically it is a border or trim in low-slope roofing.

- basilica: A Christian church building that has a nave with a semicircular apse, side aisles, a narthex and a clerestory.

- cloister: A covered walk, especially in a monastery, with an open colonnade on one side that runs along the walls of the buildings that face a quadrangle.

- mullion: A vertical element that forms a division between the units of a window, door, or screen, or that is used decoratively.

- triforium: A shallow, arched gallery within the thickness of an inner wall, above the nave of a church or cathedral.

- diaconicon: In Eastern Orthodox churches, the name given to a chamber on the south side of the central apse of the church, where the vestments, books, and so on that are used in the Divine Services of the church are kept.

- clerestory: The upper part of a wall that contains windows that let in natural light to a building, especially in the nave, transept, and choir of a church or cathedral.

Early Christian Architecture

After their persecution ended in the fourth century, Christians began to erect buildings that were larger and more elaborate than the house churches where they used to worship. However, what emerged was an architectural style distinct from classical pagan forms.

Architectural formulas for temples were deemed unsuitable. This was not simply for their pagan associations, but because pagan cult and sacrifices occurred outdoors under the open sky in the sight of the gods. The temple, housing the cult figures and the treasury, served as a backdrop. Therefore, Christians began using the model of the basilica, which had a central nave with one aisle at each side and an apse at one end.

Old St. Peter’s and the Western Basilica

The basilica model was adopted in the construction of Old St. Peter’s church in Rome. What stands today is New St. Peter’s church, which replaced the original during the Italian Renaissance.

Whereas the original Roman basilica was rectangular with at least one apse, usually facing North, the Christian builders made several symbolic modifications. Between the nave and the apse, they added a transept, which ran perpendicular to the nave. This addition gave the building a cruciform shape to memorialize the Crucifixion.

The apse, which held the altar and the Eucharist, now faced East, in the direction of the rising sun. However, the apse of Old St. Peter’s faced West to commemorate the church’s namesake, who, according to the popular narrative, was crucified upside down.

A Christian basilica of the fourth or fifth century stood behind its entirely enclosed forecourt. It was ringed with a colonnade or arcade, like the Greek stoa or peristyle that was its ancestor, or like the cloister that was its descendant. This forecourt was entered from outside through a range of buildings along the public street.

In basilicas of the former Western Roman Empire, the central nave is taller than the aisles and forms a row of windows called a clerestory. In the Eastern Empire (also known as the Byzantine Empire, which continued until the fifteenth century), churches were centrally planned. The Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy is prime example of an Eastern church.

San Vitale

The church of San Vitale is highly significant in Byzantine art, as it is the only major church from the period of the Eastern Emperor Justinian I to survive virtually intact to the present day. While much of Italy was under the rule of the Western Emperor, Ravenna came under the rule of Justinian I in 540.

The church was begun by Bishop Ecclesius in 527, when Ravenna was under the rule of the Ostrogoths, and completed by the twenty-seventh Bishop of Ravenna, Maximian, in 546 during the Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna. The architect or architects of the church is unknown.

The construction of the church was sponsored by a Greek banker, Julius Argentarius, and the final cost amounted to 26,000 solidi (gold pieces). The church has an octagonal plan and combines Roman elements (the dome, shape of doorways, and stepped towers) with Byzantine elements (a polygonal apse, capitals, and narrow bricks). The church is most famous for its wealth of Byzantine mosaics —they are the largest and best preserved mosaics outside of Constantinople.

The central section is surrounded by two superposed ambulatories, or covered passages around a cloister. The upper one, the matrimoneum, was reserved for married women.

A central plan has the nave in a circle around the open center. There is an apse and altar placed on one wall with a long narthex, or porch, on an angle to the main octagonal building. San Vitale is known for its rich decoration on the interior of mosaics and inlaid marble.

A series of mosaics in the lunettes above the triforia depict sacrifices from the Old Testament.

On the side walls, the corners, next to the mullioned windows, are mosaics of the Four Evangelists, who are dressed in white under their symbols (angel, lion, ox and eagle). The cross-ribbed vault in the presbytery is richly ornamented with mosaic festoons of leaves, fruit, and flowers that converge on a crown that encircles the Lamb of God.

The crown is supported by four angels, and every surface is covered with a profusion of flowers, stars, birds, and animals, specifically many peacocks. Above the arch , on both sides, two angels hold a disc. Beside them are representations of the cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem. These two cities symbolize the human race. For a good video explanation of San Vitale visit: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and- colonial-americas/medieval-europe-islamic-world/v/justinian-and-his-attendants- 6th-century-ravenna

The Justinian and Theodora Mosaics, San Vitale

These mosaics are located on the east end on either side of the altar. Although Emperor Justinian I and his Empress Theodora never visited Ravenna their presence in these mosaics suggests that their influence is strong in the West as well as the East. Justinian sent his general Belisarius to rout the Aryan Visigoths led by Emperor Theodoric, who had himself been a hostage for many years as a youth in the court of Constantinople. Balisarius was finally successful but not until some 25 years after Theodoric’s death.

Note that the mosaics are situated in such a way that the Emperor and Empress each move toward each other and toward the altar in the center of the apse. Theodoric holds a vessel like that used to hold the wafers in the Eucharist; Theodora holds a chalice like those that would hold the wine/blood of Christ. In fact, only Justinian would have been able to physically approach the altar as women were confined to a space in the balcony or well away from the altar. Despite this tradition, Theodora appears to have had almost a co-equal share in the rule of the Empire even though she was reputed to be of low birth and had been an actress – possibly a euphemism for prostitute – and Justinian’s long-time mistress before he married her. The video gives more detail about the Byzantine style of the figures.

Sculpture of the Early Christian Church

Despite an early opposition to monumental sculpture, artists for the early Christian church in the West eventually began producing life-sized sculptures.

Key Points

- Early Christians continued the ancient Roman traditions in portrait busts and sarcophagus reliefs, as well as in smaller objects such as the consular diptych.

- The Carolingian and Ottonian eras witnessed a return to the production of monumental sculpture. By the tenth and eleventh centuries, there are records of several apparently life-size sculptures in Anglo-Saxon churches.

- Monumental crosses sculpted from wood and stone became popular during the ninth and tenth centuries in Germany, Italy, and the British Isles.

Key Terms

- diptych: A pair of linked panels, generally in ivory, wood, or metal and decorated with rich sculpted decoration.

- sculpture in the round: Free-standing sculpture, such as a statue, that is not attached (except possibly at the base) to any other surface.

- Iconoclasm: the destruction of icons, or religious imagery.

The Early Christians were opposed to monumental religious sculpture. Nevertheless, they continued the ancient Roman sculptural traditions in portrait busts and sarcophagus reliefs. Smaller objects, such as consular diptychs, were also part of the Roman traditions that the Early Christians continued.

Small Ivory Reliefs

Carolingian art revived ivory carving, often in panels for the treasure bindings of grand illuminated manuscripts, as well as in crozier (bishop’s staff) heads and other small fittings. The subjects were often narrative religious scenes in vertical sections, largely derived from Late Antique paintings and carvings, as were those with more hieratic images derived from consular diptychs and other imperial art.

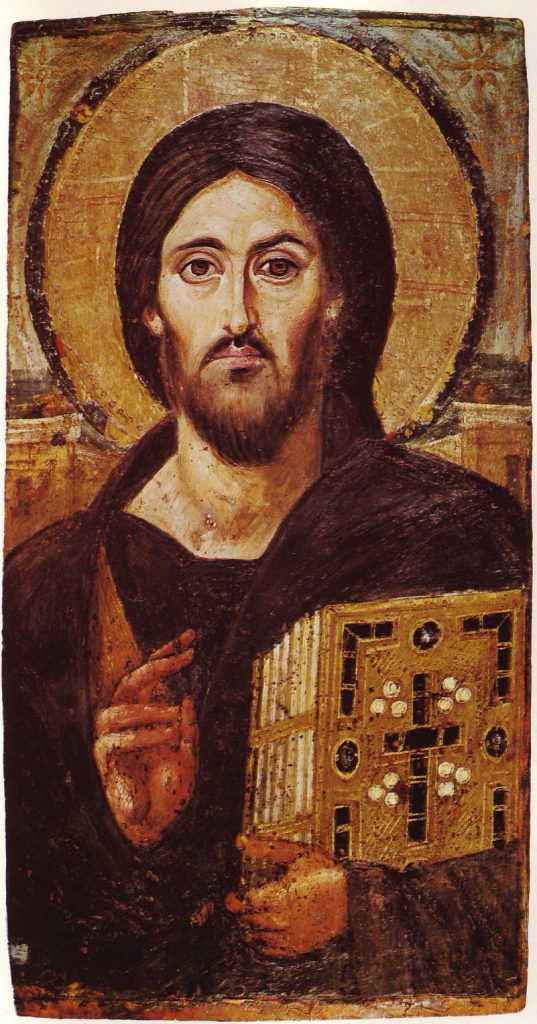

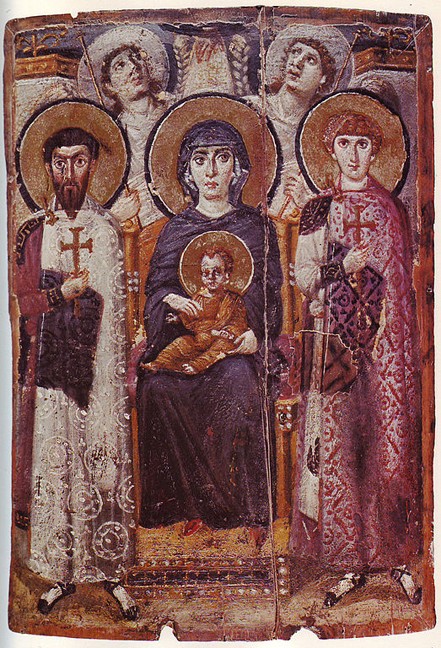

Byzantine examples of ivory icons provide an early idea into the figurative style of the period, and into the very early Renaissance. Icons could be private objects of worship and as such suffered from much handling. They eroded over time from human contact including kissing that was meant to bring the devotee into closer contact with their god. During an outbreak of iconoclasm, or the destruction of objects of worship, initiated by Leo III during the 8th c. CE, many of these objects were destroyed. Justinian I had established the first monastery in Egypt, St. Catherine’s, and collected many of the most beautiful icons there. They escaped Leo’s attention and have survived.

This typical composition shows Mary, the Queen of Heaven, on a throne with the Christ Child surrounded by saints and angels. The angels here behind Mary are particularly interesting because they tilt their faces upward to God but in a ¾ view instead of the usual frontal position. Mary is in purple to suggest her Heavenly Royalty. Note the large, Byzantine eyes, the schematic linear features and the columnar (like a column), weightless body-types.

Another icon saved at St. Catherine’s is this one of Christ Pantokrator. Ruler of All or All-Powerful. This is typical of the image with gesture of blessing and holy book. Note the disparities or differences between the two sides of the face – one is smooth and perfect, the other rough, dark, and a little misshapen. The sides correspond to the gestures of the figure with the blessing – the Heavenly gesture – on the perfect side and the imperfect side holds the Bible or word of God meant for human beings here on Earth – the earthly realm v. the Heavenly. It suggests very subtly the dual nature of Christ – mortal and god.