14 Ancient Egypt

Introduction to Ancient Egyptian Art

Ancient Egyptian art is the painting, sculpture, and architecture produced by the civilization in the Nile Valley from 5000 BCE to 300 CE.

Key Points

- Ancient Egyptian art reached considerable sophistication in painting and sculpture , and was both highly stylized and symbolic.

- The Nile River, with its predictable flooding and abundant natural resources, allowed the ancient Egyptian civilization to thrive sustainably and culturally. Much of the surviving art comes from tombs and monuments; hence, the emphasis on life after death and the preservation of knowledge of the past. In a narrower sense, Ancient Egyptian art refers to the second and third dynasty art developed in Egypt from 3000 BCE and used until the third century.

- Most elements of Egyptian art remained remarkably stable over this 3,000 year period, with relatively little outside influence.

Key Terms

- wadi: A valley, gully, or stream bed in northern Africa and southwest Asia that remains dry except during the rainy season.

- Ancient Egypt: A civilization that existed in the valley of the Nile River from 3150 BC to 30 BC. Noted for building the Great Pyramids of Giza.

- pyramid: An ancient massive construction with a square or rectangular base and four triangular sides meeting in an apex, such as those built as tombs in Egypt or as bases for temples in Mesoamerica.

Ancient Egypt

In Ancient Egypt , the Bronze Age began in the Protodynastic period circa 3,150 BCE. The hallmarks of ancient Egyptian civilization, such as art, architecture, and many aspects of religion, took shape during the Early Dynastic period and lasted until about 2,686 BCE. During this period, the pantheon of the gods was established and the illustrations and proportions of their human figures developed; and Egyptian imagery , symbolism , and basic hieroglyphic writing were created. During the Old Kingdom, from 2686-2181 BCE, the Egyptian pyramids and other more natural sculptures were built. The first-known portraits were also completed. At the end of the Old Kingdom, the Egyptian style moved toward formalized seminude figures with long bodies and large eyes.

Ancient Egyptian art includes the painting, sculpture, architecture, and other arts produced by the civilization in the lower Nile Valley from 5000 BCE to 300 CE. Ancient Egyptian art reached considerable sophistication in painting and sculpture, and was both highly stylized and symbolic. Much of the surviving art comes from tombs and monuments; hence, the emphasis on life after death and the preservation of knowledge of the past. In a narrower sense, Ancient Egyptian art refers to art of the second and third dynasty developed in Egypt from 3000 BCE until the third century. Most elements of Egyptian art remained remarkably stable over this 3,000 year period, with relatively little outside influence. The quality of observation and execution began at a high level and remained so throughout the period.

Ancient Egypt was able to flourish because of its location on the Nile River, which floods at predictable intervals, allowing controlled irrigation, and providing nutrient-rich soil favorable to agriculture. Most of the population and cities of Egypt lie along those parts of the Nile valley north of Aswan, and nearly all the cultural and historical sites of Ancient Egypt are found along riverbanks. The Nile ends in a large delta that empties into the Mediterranean Sea. The settlers of the area were able to eventually produce a surplus of edible crops, which in turn led to a growth in the population. The regular flooding and ebbing of the river is also responsible for the diverse natural resources in the region.

Natural resources in the Nile Valley during the rise of ancient Egypt included building and decorative stone, copper and lead ores, gold, and semiprecious stones, all of which contributed to the architecture, monuments, jewels, and other art forms for which this civilization would become well known. High-quality building stones were abundant. The ancient Egyptians quarried limestone all along the Nile Valley, granite from Aswan, and basalt and sandstone from the wadis (valleys) of the eastern desert. Deposits of decorative stones dotted the eastern desert and were collected early in Egyptian history.

The Prehistory of Egypt spans the period of earliest human settlement to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt in ca. 3100 BCE, beginning with King Menes/Narmer. The Predynastic Period is traditionally equivalent to the Neolithic period, beginning ca. 6000 BCE and is generally divided into cultural periods, each named after the place where a certain type of Egyptian settlement was first discovered. However, the same gradual development is present throughout the entire Predynastic period, and individual “cultures” must not be interpreted as separate entities but as largely subjective divisions used to facilitate the study of the entire period.

Old Kingdom

The Old Kingdom is the name given to the period in the third millennium BCE when Egypt attained its first continuous peak of civilization in complexity and achievement—the first of three so-called “Kingdom” periods which mark the high points of civilization in the lower Nile Valley (the others being Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom). While the Old Kingdom was a period of internal security and prosperity, it was followed by a period of disunity and relative cultural decline referred to by Egyptologists as the First Intermediate Period. During the Old Kingdom, the king of Egypt (not called the Pharaoh until the New Kingdom) became a living god, who ruled absolutely and could demand the services and wealth of his subjects. Under King Djoser, the first king of the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, the royal capital of Egypt was moved to Memphis. A new era of building was initiated at Saqqara under his reign. King Djoser’s architect, Imhotep, is credited with the development of building with stone and with the conception of the new architectural form—the Step Pyramid . Indeed, the Old Kingdom is perhaps best known for the large number of pyramids constructed at this time as pharaonic burial places. For this reason, the Old Kingdom is frequently referred to as “the Age of the Pyramids.”

Sculpture in the Old Kingdom set the standard for all sculpture to come – except for the moment of Akhenaten and Amarna. One of the Great Pyramids at Giza was the tomb of Menkaure (Mycerinus). This iconic greywacke relief sculpture of Menkaure and one of his queens shows the characteristics of Egyptian pharoanic sculpture. He is rigid, frontal, with one foot forward as a sign of life. The queen’s gesture is one of familial belonging rather than protection.

Middle Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt is the period in the history of ancient Egypt stretching from the establishment of the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Thirteenth Dynasty, between 2055 and 1650 BCE. During this period, the funerary cult of Osiris rose to dominate Egyptian popular religion.

New Kingdom

The New Kingdom of Egypt, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire, is the period between the sixteenth century and the eleventh century BCE, covering the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of Egypt. The New Kingdom followed the Second Intermediate Period and was succeeded by the Third Intermediate Period. It was Egypt’s most prosperous time and marked the peak of its power.

The Ptolemaic dynasty was a Macedonian Greek royal family which ruled the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt during the Hellenistic period. Their rule lasted for 275 years, from 305 BCE to 30 BCE. They were the last dynasty of ancient Egypt.

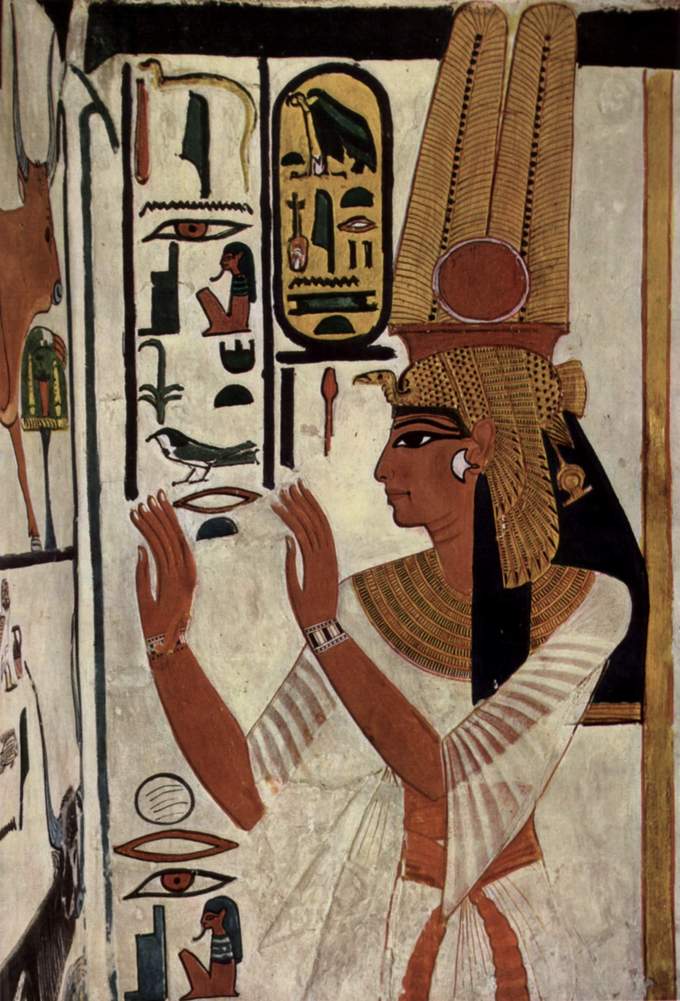

Painting

All Egyptian reliefs were painted, and less prestigious works in tombs, temples, and palaces were just painted on a flat surface. Stone surfaces were prepared by whitewash, or, if rough, a layer of coarse mud plaster, with a smoother gesso layer above; some finer limestones could take paint directly. Pigments were mostly mineral, chosen to withstand strong sunlight without fading. The binding medium used in painting remains unclear; egg tempera and various gums and resins have been suggested. It is clear that true fresco, painted into a thin layer of wet plaster, was not used. Instead, the paint was applied to dried plaster, in what is called fresco a secco in Italian. After painting, a varnish or resin was usually applied as a protective coating, and many paintings with some exposure to the elements have survived remarkably well, although those on fully exposed walls rarely have. Small objects including wooden statuettes were often painted using similar techniques.

See http://www.britishmuseum.org/visiting/galleries/ancient_egypt/room_61_tomb-chapel_nebamun/nebamun_animation.aspx for an interactive recreation of what Nebamun’s funeral chapel might have looked like.

Many ancient Egyptian paintings have survived due to Egypt’s extremely dry climate. The paintings were often made with the intent of making a pleasant afterlife for the deceased. The themes included journey through the afterworld or protective deities introducing the deceased to the gods of the underworld (such as Osiris). Some tomb paintings show activities that the deceased were involved in when they were alive and wished to carry on doing for eternity. Egyptian paintings are painted in such a way to show a profile view and a side view of the animal or person—a technique known as composite view. Their main colors were red, blue, black, gold, and green.

Sculpture

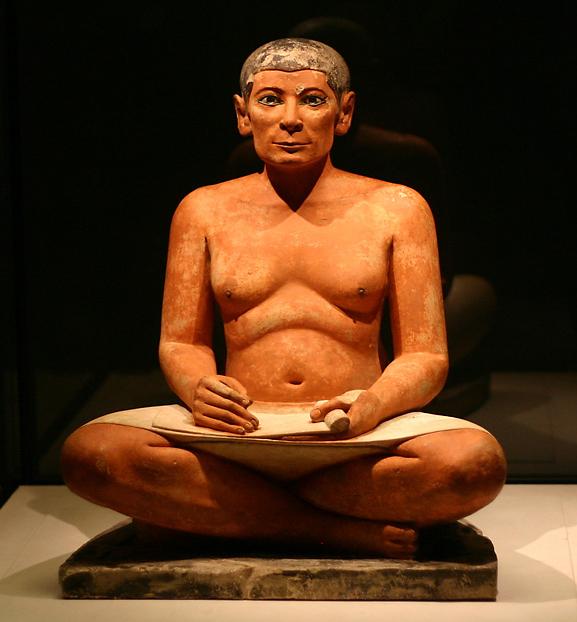

The monumental sculpture of Ancient Egypt is world famous, but refined and delicate small works exist in much greater numbers. The Egyptians used the distinctive technique of sunk relief, which is well suited to very bright sunlight. The main figures in reliefs adhere to the same figure convention as in painting, with parted legs (where not seated) and head shown from the side, but the torso from the front, and a standard set of proportions making up the figure, using 18 “fists” to go from the ground to the hair-line on the forehead. This appears as early as the Narmer Palette from Dynasty I, but elsewhere the convention is not used for minor figures shown engaged in some activity, such as the captives and corpses. Other conventions make statues of males darker than females. Very conventionalized portrait statues appear from as early as Dynasty II (before 2,780 BCE), and, with the exception of the art of the Amarna period of Ahkenaten and some other periods such as Dynasty XII, the idealized features of rulers changed little until after the Greek conquest.

By Dynasty IV (2680–2565 BCE) at the latest, the idea of the Ka statue was firmly established. These were put in tombs as a resting place for the ka portion of the soul. The so-called reserve heads, or plain hairless heads, are especially naturalistic, though the extent to which there was real portraiture in Ancient Egypt is still debated.

Early tombs also contained small models of the slaves, animals, buildings and objects – such as boats necessary for the deceased to continue his lifestyle in the afterworld – and later Ushabti figures. However, the great majority of wooden sculpture has been lost to decay, or probably used as fuel. Small figures of deities, or their animal personifications, are commonly found in popular materials such as pottery . There were also large numbers of small carved objects, from figures of the gods to toys and carved utensils. Alabaster was often used for expensive versions of these, while painted wood was the most common material, normally used for the small models of animals, slaves, and possessions that were placed in tombs to provide for the afterlife.

Very strict conventions were followed while crafting statues, and specific rules governed the appearance of every Egyptian god. For example, the sky god (Horus) was essentially to be represented with a falcon’s head, while the god of funeral rites (Anubis) was to be always shown with a jackal’s head. Artistic works were ranked according to their compliance with these conventions, and the conventions were followed so strictly that, over three thousand years, the appearance of statues changed very little. These conventions were intended to convey the timeless and non-aging quality of the figure’s ka.

The monumental sculpture of Ancient Egypt is world famous, but refined and delicate small works exist in much greater numbers. The Egyptians used the distinctive technique of sunken relief, which is well suited to very bright sunlight. The main figures in reliefs adhere to the same figure convention as in painting, with parted legs (where not seated) and head shown from the side, but the torso from the front, and a standard set of proportions making up the figure, using 18 “fists” to go from the ground to the hair-line on the forehead. This appears as early as the Narmer Palette from Dynasty I (c. 31st century BCE), but there, as elsewhere, the convention is not used for minor figures shown engaged in some activity, such as the captives and corpses. Other conventions make statues of males darker than females. Figures shown from multiple perspectives – head in profile, shoulders front, legs and feet in profile – are called composite figures.

Early tombs contained small sculptural models of the slaves, animals, buildings, and objects, such as boats necessary for the deceased to continue his lifestyle in the afterlife, and later Ushabti figures. However, the great majority of wooden sculpture has been lost to decay, or probably used as fuel. Small figures of deities, or their animal personifications, are commonly found in popular materials such as pottery. There were also large numbers of small carved objects, from figures of the gods to toys and carved utensils. Alabaster was often used for expensive versions of these, while painted wood was the most common material, normally used for the small models of animals, slaves, and possessions that were placed in tombs to provide for the afterlife.

Architecture of the New Kingdom

The golden age of the New Kingdom created huge prosperity for Egypt and allowed for the proliferation of monumental architecture.

It is the period of Hatshepsut, Tutankhamun, Ramses II, and other famous pharaohs. The wealth gained through military dominance created huge prosperity for Egypt and allowed for the proliferation of monumental architecture, especially works that glorified the pharaohs’ achievements. Starting with Hatshepsut, buildings were of a grander scale than anything previously seen in the Middle Kingdom.

The Valley of the Kings

By this time, pyramids were no longer built by kings, but they continued to build magnificent tombs. This renowned valley in Egypt is where, for a period of nearly 500 years, tombs were constructed for the Pharaohs and powerful nobles of the New Kingdom. The valley is known to contain 63 tombs and chambers, the most well known of which is the tomb of Tutankhamun (commonly known as King Tut). Despite its small size, it is the most complete ancient Egyptian royal tomb ever found. In 1979, the Valley became a World Heritage Site, along with the rest of the Theban Necropolis.

Hatshepsut

Sculpture in the New Kingdom continued in the traditional Egyptian style, with many great works produced by pharaohs over the years. However, during the later Amarna period, it underwent a drastic shift in style to emphasize more naturalistic (and less idealistic) human figures, such as those with drooping bellies. While reliefs and sculptures in the round continued to be painted, the skin tones of male and female figures was now the same value of brown. Some scholars believe that the shift was due to a new group of artists whose training was different from those trained in the traditional methods at Karnak.

Hatshepsut’s (1508–1458 BCE) construction of statues was so prolific that, today, almost every major museum in the world has a statue of hers among their collections. While some statues show her in typically feminine attire, others depict her in the royal ceremonial attire. The physical aspect of the gender of pharaohs was rarely stressed in the art, and with few exceptions, subjects were idealized. The Osirian statues of Hatshepsut, located at her tomb, follow the Egyptian tradition of depicting the dead pharaoh as the god Osiris. However, many of the official statues commissioned by Hatshepsut show her less symbolically, and more naturally, as a woman in typical dresses of the nobility of her day.

The Temple of Hatshepsut was Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple and was the first to be built in the area. The focal point of the tomb was the Djeser-Djeseru, a colonnaded structure of perfect harmony that predates the Parthenon by nearly one thousand years. Built into a cliff face, Djeser-Djeseru, or “the Sublime of Sublimes,” sits atop a series of terraces that once were graced with lush gardens. Funerary goods belonging to Hatshepsut include a lioness “throne,” a game board with carved lioness head, red-jasper game pieces bearing her title as Pharaoh, a signet ring, and a partial shabti figurine bearing her name.

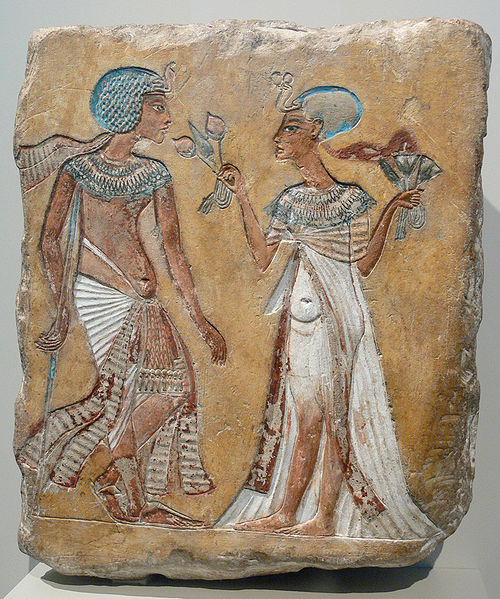

Amarna Art

The style of sculpture shifted drastically during the Amarna Period in the late Eighteenth Dynasty , when Pharaoh Akhenaten moved the capital to the city of Amarna. This art is characterized by a sense of movement and activity in images, with figures having raised heads, many figures overlapping, and many scenes full and crowded. Sunken relief was widely used. Figures are depicted less idealistically and more realistically, with an elongation and narrowing of the neck; sloping of the forehead and nose; prominent chin; large ears and lips; spindle-like arms and calves; and large thighs, stomachs, and hips. For example, many depictions of Akhenaten’s body show him with wide hips, a drooping stomach, thick lips, and thin arms and legs. This is a divergence from the earlier Egyptian art which shows men with perfectly chiseled bodies, and there is generally a more “feminine” quality in male figures. Some scholars suggest that the presentation of the human body as imperfect during the Amarna period is in deference to Aten.

Like previous works, faces on reliefs continued to be shown exclusively in profile. The illustration of figures’ hands and feet showed great detail, with fingers and toes depicted as long and slender. The skin color of both males and females was generally dark brown, in contrast to the previous tradition of depicting women with lighter skin. Along with traditional court scenes, intimate scenes were often portrayed. In a relief of Akhenaten, he is shown with his primary wife, Nefertiti, and their children in an intimate setting. His children are shrunken to appear smaller than their parents, a routine stylistic feature of traditional Egyptian art.

While the religious changes of the Amarna period were brief, the styles introduced to sculpture had a lasting influence on Egyptian culture.

Akhenaten’s extraordinary upheaval of Egyptian pictorial, religious, and governmental tradition lived only as long as he did. His son (by another wife, not Nefertiti) took everything back the way it had been before his father’s rule. He was a short-lived pharaoh, but one that left a very big impression on the world.

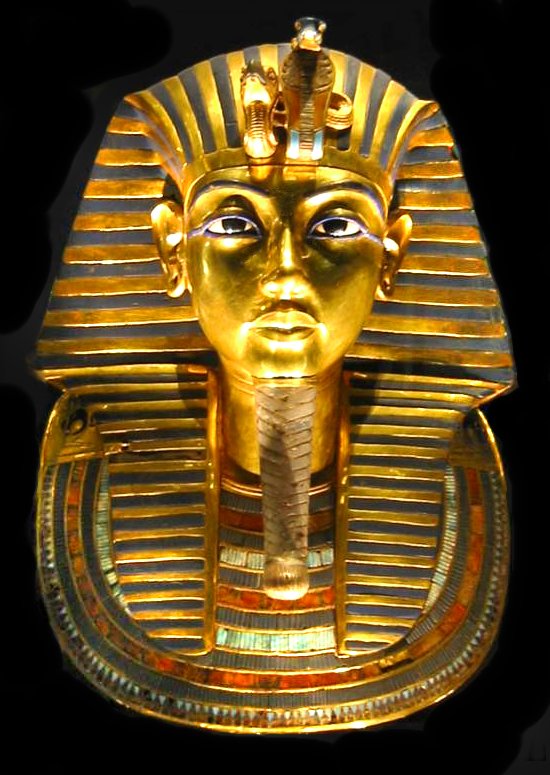

Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun was an Egyptian pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty, who ruled from around 1332 BC to 1323 BCE. Popularly referred to as “King Tut,” the boy-king took the throne when he was nine and ruled until his early death at age nineteen. Tutankhamun was buried in a tomb that was small relative to his status. His death may have occurred unexpectedly, before the completion of a grander royal tomb, so that his mummy was buried in a tomb intended for someone else. His mummy still rests in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings, though is now on display in a climate-controlled glass box rather than his original golden sarcophagus . Relics and artifacts from his tomb, including his pectoral jewels and a red granite lion, are among the most traveled artifacts in the world.

Painted walls in the burial chamber of Tutankhamun’s tomb, Valley of the Kings, Egypt (late 14th century BCE): Tutankhamun’s burial chamber contained beautiful works of art, text, and hieroglyphics.