21 Gothic Art and Architecture

Gothic Architecture

Europe c. 1200

The 13th century in Europe was a time of invention, but also unrest. Scholasticism began the process of reconciling classical philosophy with Christian teachings. This would continue during the Renaissance as Neoplatonism. It is the century that saw the Fourth Crusade (1202-1204) through the Ninth Crusade (1271-1272); many of these Crusades which were ostensibly meant to take the Holy Land back from the Muslims weren’t always as advertised. The Fourth Crusade saw the Crusaders rerouted because of various political and economic reasons into a sack of the Christian city of Constantinople. The Children’s Crusade (2012) never made it to the Middle East and saw many of the children taken into slavery or victims of other tragic circumstances. This century saw the rise of the mendicant (took vows of poverty) orders of monks – the Franciscans, Dominicans, Augustinians, and the Carmelites. The writings of Roger Bacon and Thomas Aquinas are from this period, Genghis Khan’s army invaded Russia, and the population of Western Europe grew significantly. Still a feudal economy, farming methods advanced including the use of a heavier plow and horses – something actually pictured in the Bayeux Tapestry.

This is also the moment when church architecture in Western Europe turns from the Romanesque to the more elaborate forms of the Gothic.

Abbot Suger

Abbot Suger (pr. Soo’-jhay; circa 1081-1151), Abbot of Saint Denis located just outside Paris from 1122 and a friend and confidant of French kings, began work around 1135 on rebuilding and enlarging the abbey church. Saint Denis was the traditional burial place of French kings, and as such Suger determined that the old Romanesque church was too low, too dark and not ornate enough to honor both the royal occupants and their God. He set out to remodel and in the act created a form of ecclesiastical architecture that would become the inspiration all over Europe for centuries.

Suger was the patron of the rebuilding of Saint Denis, but not the architect, as was often assumed in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In fact it appears that two distinct architects, or master masons, were involved in the 12th century changes. Both remain anonymous, but their work can be distinguished stylistically.

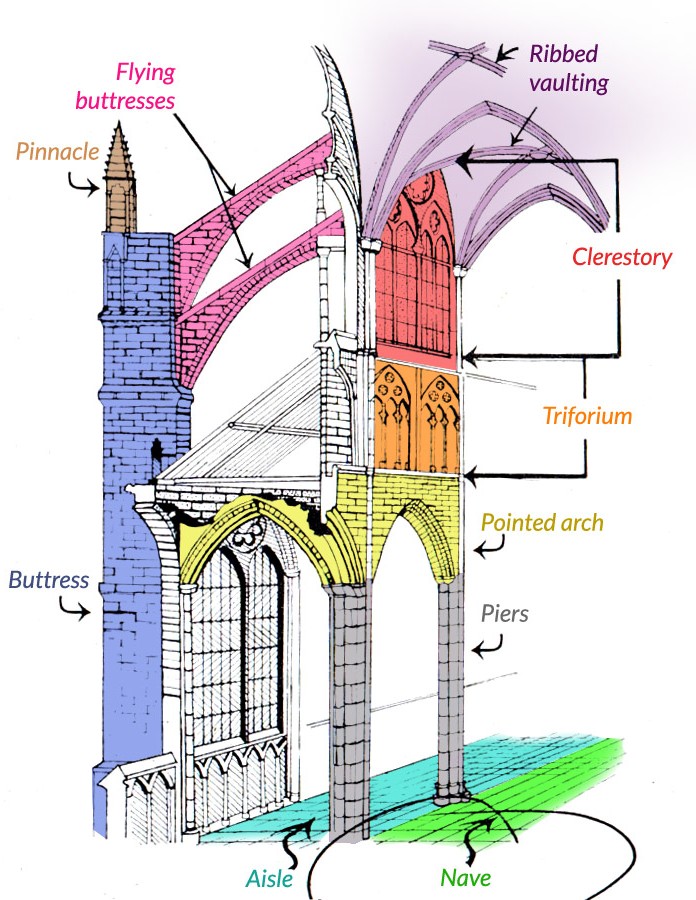

Suger’s western extension was completed in 1140 and the three new chapels in the narthex were consecrated on June 9th of that year. On completion of the west front, Abbot Suger moved on to the reconstruction of the eastern end. He wanted a choir (chancel) that would be suffused with light. To achieve his aims, Suger’s masons drew on the new elements that had evolved or been introduced to Romanesque architecture: the pointed arch, the ribbed vault, the ambulatory with radiating chapels, the clustered columns supporting ribs springing in different directions, and the flying buttresses, which enabled the insertion of large clerestory windows. This was the first time that these features had all been brought together. The new structure was finished and dedicated on June 11th of 1144, in the presence of the King.

Thus, the Abbey of Saint Denis became the prototype for further building in the royal domain of northern France. Through the rule of the Angevin dynasty, the style was introduced to England and spread throughout France, the Low Countries, Germany, Spain, northern Italy, and Sicily.

The dark Romanesque nave, with its thick walls and small window openings, was rebuilt using the latest techniques, in what is now known as Gothic. This new style, which differed from Suger’s earlier works as much as they had differed from their Romanesque precursors, reduced the wall area to an absolute minimum. Flying buttresses removed the load of the upper structure away from the walls and into the ground allowing for the walls to be pierced by large windows. The vast window openings were filled with brilliant stained glass and interrupted only by the most slender of bar tracery—not only in the clerestory but also, perhaps for the first time, in the normally dark triforium level. The upper facades of the two much-enlarged transepts were filled with two spectacular rose windows. As with Suger’s earlier rebuilding work, the identity of the architect or master mason is unknown.

The abbey is often referred to as the “royal necropolis of France” as it is the site where the kings of France and their families were buried for centuries. All but three of the monarchs of France from the 10th century until 1789 have their remains here. The effigies of many of the kings and queens are on their tombs, but during the French Revolution, those tombs were opened and the bodies were moved to mass graves.

Sculpture

Surfaces of Gothic churches were decorated with sculpture that was meant to be didactic – it reinforced the lessons of the church for both the literate and illiterate as they entered and left the building. One site that was particularly useful was around and above the portals. In the following examples from Chartres Cathedral in France you see the change that figurative sculpture underwent during the decades and sometimes centuries it took to build a Cathedral.

The sculpture from the 12th century is columnar, carved tightly to the column it stands in front of. The figures aren’t differentiated substantially and they are weightless. The drapery is linear, as it is in Byzantine images, and it doesn’t describe the bodies underneath.

In the 13th c. figures differences begin to emerge. The figures seem to move further from their support and gestures are specific to the figure. While still quite rigid and frontal, the figures of Stephen, Clement, and Lawrence above begin to display more movement. St. Theodore on the left is significantly different from the others. Dressed as a knight, he stands in modest contrapposto and the folds of his tabard follow the swing of his hips. His face evidences a fullness and seems to be more individualized than earlier models. He stands firmly on this two feet and turns away from the surface of the façade to engage the viewers as they enter.

By the Late Gothic period sculpture begins to return to a semblance of naturalism and a suggestion of the Classical figures of ancient Greece and Rome.

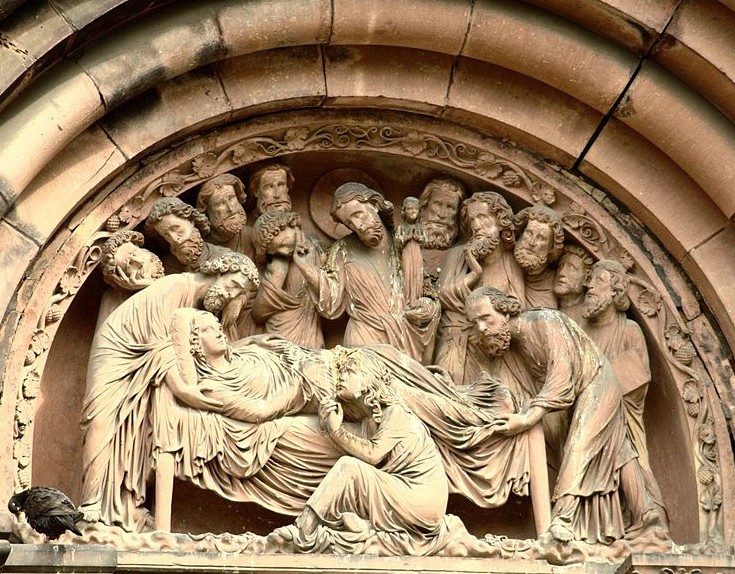

Strasbourg Cathedral’s South portal tympanum has a “Death” or Dormition of the Virgin Mary that exhibits a significant shift from the medieval figurative style of the 12th c. The figures have weight, drapery reveals the bodies underneath and while the space and arrangement of figures in that space are not naturalistic, there is more of an effort to create a scene that suggests an event rather than an abstract representation of an idea. Mary looks like a reclining Roman matron recalling the figure of Hestia from the Parthenon.

Stained Glass

With the load removed from the walls of Gothic churches by the flying buttresses they were able to be pierced by larger and more numerous openings. Suger’s wish for the metaphorical light of Heaven to shine into the church could be fulfilled.

Stained glass artists would create designs and lay lead strips along them between which they would fit glass colored with metallic salts. Stories from the Bible and images of Kings and Queens were included in the subjects for windows in Gothic cathedrals.

Secular Architecture

Gothic motifs also were applied to non-religious architecture. Jacques Coeur was a wealthy 15th c. merchant who became Charles VII’s master of the mint. At the height of his success he had the largest fortune ever amassed in France and a fleet of trading ships. Not unexpectedly, he also acquired many enemies and when in February 1450 Agnès Sorel, the King’s mistress, suddenly died, Coeur’s enemies convinced the King that Coeur had had her poisoned. More charges of financial crimes were heaped on and Coeur was ultimately sentenced to prison, a huge fine, and the confiscation of all his property.2 Ultimately, he escaped prison and ended in Rome where he was received as a hero and made captain of a fleet of military ships. Sadly, Coeur himself came down with an illness and died during the campaign.

The house of Jacques Coeur in Bourges, France, is an excellent example of the Flamboyant Style of Late Gothic architecture. “Flamboyant” means “flamelike” and Refers to the ornamentation on the exterior of the building. Pointed arches in windows and narrow towers with long pointed roofs suggest the style.

Secular Decorative Objects

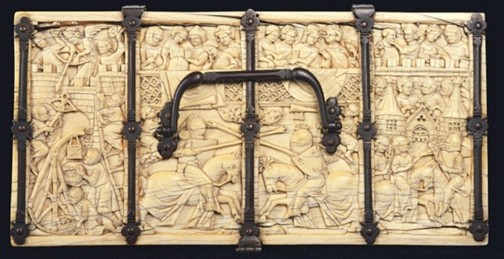

The concept of courtly love began in areas of present-day France in the 11th century. Originally a literary genre to entertain nobility, the idea spread throughout Europe and continues today in stories of knights and their ladies. In practice, not always so dedicatedly platonic – that is, love never consummated but always on a higher moral plane – that idea was none-the-less the model and conceit. Linked to brave deeds done for fair ladies, the popular concept was recounted in literature, poetry, and songs of troubadours. It has become popularized in the modern imagination with the court of King Arthur and the romance of Arthur, Lancelot, and Guinevere.

In this jewelry casket (box), the lid and four sides are carved from ivory with scenes depicting the idea of courtly love and scenes from famous lovers of history. The lid pictures a Castle with knights jousting for the favor of the ladies who watch from the battlements above. On the left clever cupid provides flowers for soldiers to hurl upward with their trebuchet.

The Unicorn Tapestries

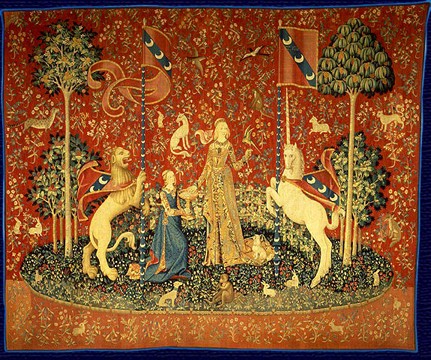

Unlike the Bayeux Tapestries, the Unicorn Tapestries are true tapestries, woven on a loom for the wealthy La Viste family of France. Created between 1484 and 1500, these panels were a series of six Flemish tapestries using the medieval meme of the Unicorn and the Virgin to also describe the senses. Sometimes the Hunt for the Unicorn is taken to be a Christian overlay of a medieval subject with the Unicorn standing for the Passion of Christ. The multitude of flowers that surround the figures is known as the “mille fleurs” style. The rampant lion bears the sigil of the La Viste family and may represent the son included in the chaste quest for the Virgin.

Italian Gothic Painting

Italian Gothic painting developed a distinctively western character and flourished from the second half of the 13th century onward.

Key Points

- The transition from the Romanesque to the Gothic style of painting happened quite slowly in Italy because Italy was strongly influenced by Byzantine art, especially in painting.

- The initial changes to the Byzantine-inspired Romanesque style were quite small, marked merely by an increase in Gothic ornamental detailing rather than a dramatic difference in the style of figures and compositions.

- Cimabue of Florence and Duccio of Siena were trained in the Byzantine style but were the first great Italian painters to break away from the Italo- Byzantine art form. They were pioneers in the move towards naturalism and depicted figures with more lifelike proportions, expressions, and shading.

- Giotto’s style represented a clear break with the Byzantine tradition, making use of foreshortening, chiaroscuro techniques, and depicting highly expressive figures.

- During the 14th century, Tuscan painting was predominantly accomplished in the International Gothic style, characterized by a formalized sweetness and grace, elegance, and richness of detail, and an idealized quality.

Key Terms

- Romanesque: Refers to the art of Europe from approximately 1000 AD to the rise of the Gothic style in the 13th century or later, depending on region.

- chiaroscuro: An artistic technique popularized during the Renaissance, referring to the use of exaggerated light contrasts in order to create the illusion of volume.

- Foreshortening: A technique for creating the appearance that the object of a drawing is extending into space by shortening the lines with which that object is drawn.

The transition from the Romanesque to the Gothic style of painting happened quite slowly in Italy, several decades after it had first taken hold in France. After the conquest of Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, the influx of Byzantine paintings and mosaics increased greatly. This was partly the reason that Italy was strongly influenced by Byzantine art, especially in painting.

The initial changes to the Byzantine-inspired Romanesque style were quite small, marked merely by an increase in Gothic ornamental detailing rather than a dramatic difference in the style of figures and compositions. Italian Gothic painting began to flourish in its own right around the second half of the 13th century with the contributions of Cimabue of Florence (ca. 1240–c a. 1302) and Duccio of Siena (ca. 1255–60–ca. 1318–19), and developed an even more strongly realistic character under Giotto (1266–1337).

Cimabue and Duccio were trained in the Byzantine style, but they were the first great Italian painters to start breaking away from the Italo-Byzantine art form. In a period when scenes and forms were still relatively flat and stylized, Cimabue was a pioneer in the move towards naturalism in Italian painting. His figures were depicted with more lifelike proportions and shading, as evident in the Crucifixion scene for the church of Santa Croce in Florence (1287-88), which demonstrates delicately shaded draperies and the chiaroscuro technique. His Maestà di Santa Trinita, a Madonna and Child painting commissioned by the church of Santa Trinita in Florence between 1290 and 1300, makes use of perspective in portraying Mary’s three-dimensional throne, and depicts the figures with sweeter and more natural expressions than typical in the somber Romanesque style.

Much like Cimabue, Duccio of Siena painted in the Byzantine style but made his own personal contributions in the Gothic style in the linearity, the rich but delicate detail, and the warm and refined colors of his work. He was also one of the first Italian painters to place figures in architectural settings. Over time, he achieved greater naturalism and softness in his work and made use of foreshortening and chiaroscuro techniques. His characters are surprisingly expressive and human, interacting tenderly with each other.

Both Cimabue and Duccio were probably influenced by Giotto in their later years. Giotto was renowned for his distinctively western style, basing his compositions not on a Byzantine tradition but, rather, on his observation of life. His figures were solidly three-dimensional, had discernible anatomy, and were clothed with garments that appear to have weight and structure. His greatest contribution to Italian Gothic art was his intense depiction of a range of emotions, which his contemporaries began to emulate enthusiastically. While painting in the Gothic style, he is considered the herald of the Renaissance.